intergenerational roots

Jane Wong is someone with deep, widespread roots.

The roots ground her in China, in the rows of crops her ancestors planted for generations. They grow deep into the fertile New Jersey soil and dig into the wet earth of the Pacific Northwest.

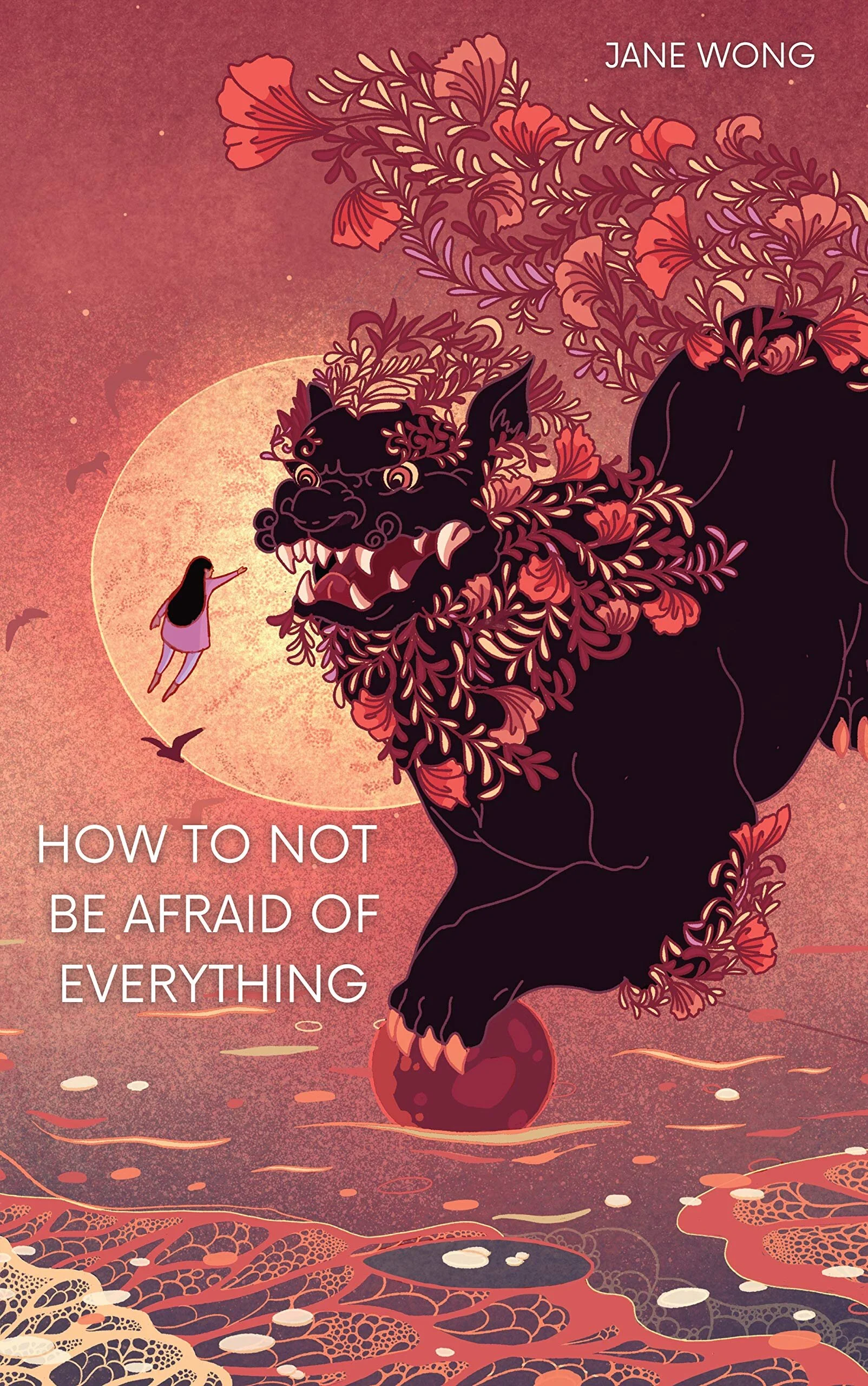

Jane Wong’s roots grow into beautiful poems about identity, memory and culture that have been published in nearly a dozen literary magazines. Her first book, Overpour, focused on the complex silhouettes you can see in the tangled roots of her upbringing. Her second book, How to Not Be Afraid of Everything, is coming out in 2021. Through poetry, Wong is dissecting her own fears in comparison to her family history.

“The book honestly, to be more blunt, combines my family’s history with my fear of men. I think they seem disconnected, but it’s that sense of feeling terrified but asking how to undo that terror, how to not be afraid of everything,” Wong says.

The poems are layered and multifaceted, Wong says. But they’re also playful, joyful even. One poem is written with blanks that your mind will fill in on its own, like a Mad Lib.

Wong is also working on a series of essays that she’ll be turning into a book, which she says is best described as “making do with what you have.” The essays talk a lot about her childhood, growing up in a Chinese restaurant in a strip mall in New Jersey.

“It’s very vulnerable. In a poem, you can hide behind a metaphor,” Wong says, “But in an essay, you have to reveal something, and more than that, you have to reflect. I think that that requires a different level of vulnerability that you have to be willing to be open to.”

One part of the creative nonfiction process Wong doesn’t love is the self-promotion she has to do. “You’re going to be tagged as ethnic literature or a children-of-immigrants story. That makes me uncomfortable because it doesn’t allow for the multiple selves, for the other parts of you to show,” she says. “I don’t feel like I fit neatly into the mold of what a stereotypical Chinese American story is.”

In one essay, what starts as pithy observations on participating in a Miss Preteen New Jersey pageant leads to a vulnerable look into Wong’s experience with whitening products, whiteness, and colorism. When she was in high school, Wong found out that all the makeup and skincare she had been using were actually skin lightening products that were bleaching her skin.

“I felt translucent, like I wasn’t fully present,” Wong says. “And if you look at pictures of me from that time, I look like a ghost.”

Another essay, entitled “Root Canal Street,” describes what it was like for Wong to visit illegal Chinese dentists on Canal Street in New York City. “I always struggle with upward mobility,” Wong says. “There’s something I will never lose about my working class upbringing, or growing up a certain way even though I’m a professor now.”

When Wong isn’t writing, she’s teaching at Western Washington University. In fact, when she’s teaching, she makes it a point to put her writing on hold. “I love teaching, and sometimes I wish I could just give a B+ version of myself to my students, but I can’t. There’s something about teaching that I just think is so vibrant and full of joy,” Wong says.

Showing students who have gone through the rote English class assignments of public school how freeing and expressive poetry can be is just as important as working on her own poetry, she says. Any prompt she gives her students she also completes as well. “It’s art, and you should be proud of the art you created,” Wong says.

In the summer, all Wong does is write. She’s attended several residencies over the years, including U.S. Fulbright Program, Artist Trust and 4Culture. “It’s magical, truly,” she says. “The whole point is that you really make your art a priority. I feel super lucky to have summers off.”

As her work progresses, Wong continues to think of her writing juxtaposed to the perceptions of her identity. “I deserve permission to write about whatever I want. Sometimes as a writer of color people expect you’re always going to be writing about identity and difficulty and trauma,” she says. “Part of the resistance is to say, ‘Yeah that’s true, and that’s part of who I am, but I also get to choose not to tell that story at times.’ I feel more and more confident to write more than what is expected of me.”